Since January this year, nearly 880,000 men, women and children have made the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean and Aegean seas looking for a new life in European countries. Images of families enjoying their summers in Italy and Greece have been replaced by photos of overcrowded dinghies arriving on the beaches of Sicily, Lesbos and Kos. As winter descends across Europe, these images look likely to be replaced by photos of cold refugees on a journey through the Balkans looking for protection and a place to rebuild their broken lives.

Over the summer these scenes have divided Europe. While many people have rallied to provide humanitarian support, gathering clothing and raising funds for those in need, others have expressed deep concern about the scale of migration, about the impact on communities and about the threat to our security. Some political leaders have shown their support for those fleeing conflict, others have set about building fences to keep the refugees out.

So what is the issue? Is this really the biggest refugee crisis in Europe since the second world war or are people simply coming to Europe for economic reasons? Where are these people coming from and why are they arriving in such large numbers now? And why do they risk everything, including the lives of their children, by travelling across the sea rather than staying in countries such as Turkey that are relatively safe and prosperous?

The scale of the crisis

While the current crisis should not be underestimated, it is not the first time that hundreds of thousands of people have been on the move looking for a better life for themselves and their children. Many of today’s scenes are reminiscent of the last major period of unrest in Europe when conflict ripped apart the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s leading not only to the creation of more than half a dozen new countries but also the displacement of huge numbers of people, including 1.2 million Bosnian refugees, some of whom were provided with protection in the UK and elsewhere.

Largest refugee camps

A refugee camp is a temporary settlement built to receive refugees. The camps tend to develop in an impromptu fashion with the aim of meeting basic human needs for only a short time. However, some refugee camps end up existing for decades, with major implications for human rights. Some camps grow into permanent settlements and even merge with nearby older communities.

Sources: Population estimates, CIA World Factbook; refugee estimates UNHCR/UNRWA. Data extracted 20th Nov 2015.

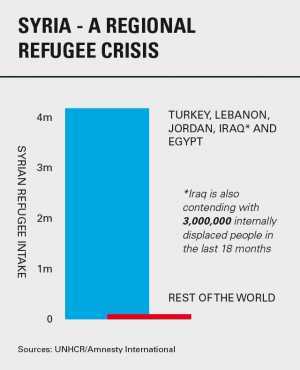

Regional refugees from the Syrian war

Over four million refugees have fled the ongoing conflict in Syria, seeking safety outside of the country they once called home. Although the British public has been saturated with stories and images about the refugee crisis in Europe, the vast majority of refugees from Syria are still hosted by Syria’s neighbouring countries. By 30 November, there were 1,075,637 refugees from Syria in Lebanon, 633,644 in Jordan and 2,181,293 in Turkey. What is sadly also typical of displacement trends around the world is that Syrian refugees are now in what is known as a protracted refugee situation, and the likelihood is that they will remain in displacement.

While the refugee crisis from the Syrian conflict has been headline news this year, other protracted refugee situations linger on silently – these include 2.6 million refugees from Afghanistan and over one million from Somalia.

There are also approximately 150,000 Sahrawi refugees who have been living in refugee camps in southwest Algeria for almost 40 years near the small military town of Tindouf. The desert-based Sahrawi camps may be invisible to many, but they have in fact been Algeria’s ‘number one tourist destination’ throughout the late-1990s and 2000s due to the enormous number of people who visit the Sahrawi refugee camps to provide humanitarian assistance and support.

Read more about Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh’s work in refugee camps on theconversation.com

Fifty years earlier the second world war created an estimated 60 million refugees; that’s 60 times greater than the refugee flows seen in Europe today. This mass movement of people did not stop with the end of the war but continued as Europe reorganised itself to accommodate the new political structures established in its wake. One year on, an estimated one million people were still unable to return to their homes.

The current crisis has historical precedents but should also be understood in a global context.

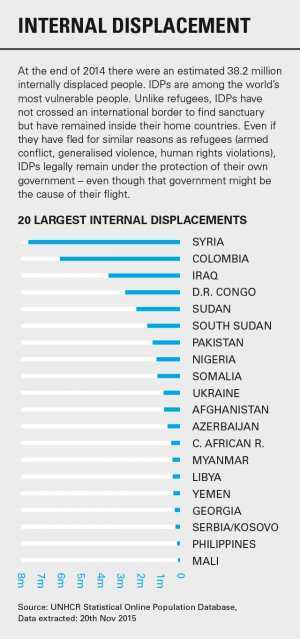

According to UNHCR – the UN’s agency for refugees – wars, conflict and persecution have forced more people to flee their homes than any other time since records began. Figures released earlier this year estimated that the number of people forcibly displaced at the end of 2014 had risen to a staggering 60 million compared to just over 50 million a year earlier and 37.5 million a decade earlier. Half of all of those forced from their homes are children.

In the past five years, at least 15 conflicts have erupted or reignited, eight in Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Central African Republic, Libya, Mali, northeastern Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and this year in Burundi), three in the Middle East (Iraq, Yemen and Syria), one in Europe (Ukraine) and three in Asia (Kyrgyzstan and in several areas of Myanmar and Pakistan).

Most of those who flee conflict do not have the economic or social resources to travel to Europe and instead seek protection in neighbouring countries and regions. Contrary to popular belief, this trend is increasing rather than decreasing: 86% of the world’s refugees are hosted in developing countries compared with 70% a decade ago. In other words, it’s becoming harder, not easier, for refugees to reach Europe.

Travelling to Europe

So why have we seen such a significant increase in the number of refugees arriving in Europe? The answer lies in large part with the conflict in Syria, which started in 2011 and has escalated over the past four years, drawing in countries within and outside the region and has been closely associated with the rise of Islamic State.

During that time more than 12 million Syrians have been forced to leave their homes. Even if they can avoid the bombs that are currently raining down on the country, those who remain in Syria are at risk of becoming ill, malnourished, abused, or exploited. Millions of children have been forced to quit school. The future looks bleak with no sign of a ceasefire. Those who have been displaced for years within the country and have been waiting for the conflict to end so they could return to their homes are starting to give up hope. They are looking for alternatives for themselves and their children.

2015 - Mediterranean Refugee crisis

Increasing numbers of refugees are taking their chance aboard unseaworthy boats and dinghies in a desperate bid to reach Europe. There are a range of nationalities travelling: many of the families arriving via Greece are Syrian and Afghan, while Eritreans and other nationalities are taking an equally perilous journey via Libya to Italy.

Sources: Population estimates, CIA World Factbook; refugee estimates UNHCR 30th Nov 2015

Image by NASA

EU and Schengen area countries

New asylum applications 2015

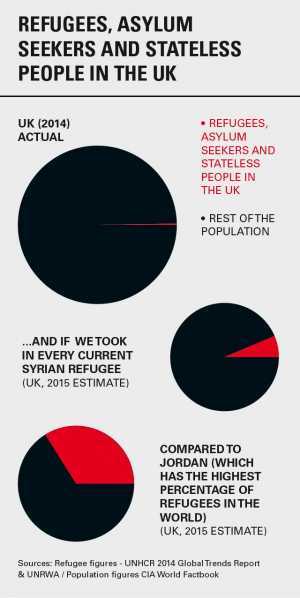

Relative to its population, so far Hungary has taken in the most refugees this year, with one refugee for every 56 citizens, followed by Sweden with one refugee for every 133 citizens. Germany has seen the largest total intake this year, the UK, meanwhile, is 21st with one refugee for every 3,333 citizens.

Sources: Eurostat Jan-Oct 2015, extracted November 2015

At least eight million people are internally displaced in Syria, while four million people have left and now live mainly in refugee camps located in the neighbouring countries. The numbers of refugees in these countries far exceeds those in the countries of Europe, particularly given the size and relative poverty of the existing population. Around one million refugees are currently living in Lebanon, a country which is half the size of Wales. And that’s just the official number. Estimates from those on the ground put the number at 1.3 million. At one point over the summer more than 20,000 Syrian refugees were arriving every 48 hours – the same number of Syrian refugees that the UK government has pledged to resettle over the next five years.

But Syria is not the only country in which there is conflict and human rights abuse. Aside from Syrians, most of those who are arriving in Greece are refugees from Afghanistan and Iraq.

In Italy the countries from which people travel are more diverse – Eritrea, Nigeria, Somalia, Gambia, Mali and Senegal – but the conditions that they leave behind are equally difficult. Human Rights Watch has recently described the situation in Eritrea as ‘dismal’. In Nigeria the militant insurgent group Boko Haram has killed civilians, abducted women and girls, forcefully conscripted young men and boys, and destroyed homes and schools, displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

Those from the countries of East and West Africa will normally have travelled for weeks, months or even years before arriving in Europe. For a time many stayed in Libya where work was plentiful and conditions were relatively stable. But following the removal from power of Colonal Gaddafi by NATO forces, Libya has experienced instability and political violence which has not only affected commerce and oil production but also increased violence, particularly towards black Africans. And it has opened up new opportunities for human smugglers and traffickers to exploit the vulnerability and desperation of refugees and migrants alike with promises of a better life elsewhere.

A difficult and dangerous journey

Across the world, border controls have made it increasingly difficult for those in need of protection to legally enter another country. And until you have entered a country that is a signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees you cannot claim asylum. For most people this means that the only way to access protection is by engaging the services of a smuggler or trafficker. The risks are high and so are the costs. Most refugees will have to sell their homes and all their possessions to raise the funds to pay for the journey across the sea. And not everyone makes it.

According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), nearly 4,000 people have died travelling across the Mediterranean from Libya to Italy or when making the short crossing across the Aegean from Turkey to the Greek islands.

So why don’t refugees stay where there are, in countries such as Libya or Turkey? Surely if they were genuine refugees they would simply wait for the conflict to end rather than travelling on into Europe putting themselves and their children at risk.

It is only possible to understand why people make the journey to Europe by talking to refugees themselves, by taking the time to find out about their lives in the countries from which they come, about the reasons why they left and what happened next.

Firstly, very few people intend to come to Europe when they first set out on their journey. What they are looking for is somewhere to feel safe and make a living for themselves and their families. For many Syrians that place remains elusive.

While many of those arriving in Europe have come directly from Damascus, Aleppo and Deraa – places where the situation has deteriorated over recent months – others have come from the refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon, where conditions have become so bad that many are considering returning to their war-ravaged homeland. But most have come from Turkey, where they have tried but failed to make a living for months or years.

Although the Turkish government allows Syrians to live in the country as ‘guests’ it retains a geographical reservation on the 1951 Convention. Ironically this means that only those from within Europe, where there is no conflict, can claim asylum. For everyone else, including the Syrians, there is no right to work, no access to education or healthcare and no possibility of a house, a business or a future. For those who have lost everything, this loss of hope pushes them on to look for somewhere that can offer them a sense of belonging and the opportunity to fulfill their potential.

Secondly, refugees know little or nothing about what awaits them in Europe. Many have previously worked as doctors, engineers, academics or have their own businesses. They are unaware of our benefits system and assume that they will need to work to support themselves and their families. In reality those seeking asylum are not allowed to work while they await a decision and are instead forced to claim benefits, losing the opportunity to build connections with people in the community, learn the language and regain their self-esteem.

Most refugees believe that if they explain what has happened to them they will be allowed to stay. The violence in their countries is, after all, well documented. In reality almost all asylum seekers have to go through a complex and expensive legal process to prove that they are at risk of persecution and should be protected. The process is complicated and many cases are refused. And most refugees think that the people of Europe will be sympathetic to their plight, that they will understand the reasons why they have abandoned their lives, their jobs and their education in order to find safety elsewhere. Unfortunately this is not the case. Despite being one of the richest regions of the world, public attitudes against refugees have hardened in recent years, driven by concerns about economic impacts and security and fuelled by misinformation about the reasons why people are coming in the first place.

A man helps to lift a young girl clear of the wire as Syrians fleeing the war try to pass through broken fences located near the Turkish Akcakale border in the southeastern Sanliurfa province.

Photograph by BULENT KILIC/AFP/Getty Images

An internally displaced family from Saladin at the new Ashti refugee camp in Iraq.

Photograph by © UNHCR/Giles Duley

A young Syrian boy sitting on the roof of his family’s new home in Zaatari refugee camp in Northern Jordan.

Photograph by © UNHCR/Christopher Herwig

Thousands of refugees are risking their lives travelling over seas in dangerously overcrowded boats.

Photograph by ©UNHCR/Benjamin Loyseau

Children make up 26% of the crossings from Turkey to Greece.

Photograph by © UNHCR/Giles Duley

Burundian refugees travelling by boat and foot to Nyarugusu refugee camp in Tanzania.

Photograph by UNHCR/Benjamin Loyseau

Syrian refugees cross the border between Greece and Macedonia, near Eidomeni. Many face violence from gangs when taking this route.

Photograph by UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

There are ways to help

The most pressing challenge is to address the root causes of migration to Europe. Since the early 1990s the EU has recognised the need for a comprehensive approach to migration addressing political, human rights and development issues in countries and regions of origin. This means reducing poverty, improving living conditions and job opportunities, preventing conflicts, consolidating democratic states and ensuring respect for human rights.

In practice, however, the focus has been fixed firmly on efforts to prevent illegal migration rather than addressing root causes and providing safe and legal access to asylum for those in need of protection.

But this is a big ask if the public believes that refugees are not genuine or that they are actually economic migrants trying to get around immigration controls. This is why information about the facts and realities of the current crisis is so important.

Migration, more than any other area of contemporary political life, can best be described as a ‘touchstone’ issue, which is to say that it represents a wide range of concerns about the modern world, a world of turbulence, insecurity and change. If ever there was an issue that represents this turbulence it is the arrival of nearly one million desperate people for whom the normalities of everyday life – school, work, family – have been torn apart.

In this context we need to make sure that we do not allow fears about what the refugee crisis represents to override our concern for our fellow human beings who are bearing the brunt of complex geo-political struggles.

We can educate ourselves about what is going on rather than believing everything we read, hear or see in a lot of mainstream media. We can join a local refugee support group to befriend and mentor those refugees who make it to the UK. We can lobby our local authority and politicians to resettle more refugees from Syria and elsewhere so they don’t end up making the difficult and dangerous journey into, and then through, Europe.

What we see and hear can feel overwhelming. It can feel like we can’t make a difference. But as every refugee will tell you, the comfort of strangers can be a powerful antidote to the pain of being forced to leave your home, your family and everything that is familiar.

Heaven Crawley is Professor of International Migration at Coventry University’s Centre for Trust, Peace & Social Relations